Some things may seem simple: a 1 year old with severe malaria, whose blood cells have been destroyed by the parasite, needs rapid attention. An IV, some highly effective medicine, a blood transfusion, monitoring. Maybe IV fluids if the blood sugar is low, or a seizure medication. But what happens when there is no medicine, no IV fluid, no tubing to carry the blood from a bag to the patient, no tube to hold a blood sample to measure the amount and type needed? What happens when there isn't even a malaria test? Step in with resources and even-out a bit of the world's injustice. The 1 year old had no option about being born in a malarial jungle, about the poor drainage around a house without windows or screens allowing mosquitoes to feast. The 1-year-old didn't choose parents who can't afford to get care anywhere but the public hospital, didn't choose to be a baby during the COVID pandemic when government medical stores are depleted, supplies are months late in arriving, transport to another hospital nearly impossible.

In fact in Bundibugyo we've been studying this problem in health care capacity-the pandemic's impact on health worker burn out, sickness, fear; the lack of supplies and diversion of resources to other places, the stress on marginal health systems; the hesitation of the population to seek care as frightening messages roll out about coronavirus, the ban on public transportation, the curfews, the falling economy, all making care difficult to access. It's a perfect storm we've seen before with Ebola, only this time the winds are pounding globally. We actually have some pretty good data that the potential collateral damage could be greater than the viral damage (as it has been for Ebola), with years of improvement in maternal and child health lost. Quite possible bad-case-scenario (I won't say worst-case, because these are mathematical models of reasonably possible events and 2020 keeps throwing us curve balls), both maternal and child deaths could increase by 38-44% this year. That would be over 2 million extra dead children.

We know that some basic interventions: food for malnutrition, antibiotics, medicines that stop blood loss in labor, a clean delivery environment . . . can prevent much of this slide. A few hundred dollars of such basics serves more than a hundred people. In fact I suppose that many of the 2 million plus lives that the COVID impact will cost could be saved with less than 8 million dollars' investment in the right places.

So the responsible thing, the just thing, would be to use all possible means to shore up the systems that are crumbling, to invest in medicines and food and vaccines that can save lives.

Which is what we do here routinely, and way moreso the last few weeks. Bundibugyo Hospital has a solid team of leaders, and we are privileged to join forces with people who are concerned about how to improve our quality of care. How to stay ahead of the problems. How to work together.

But yesterday, I saw that a meeting for the Paeds ward staff had been called. I texted the in-charge nurse to see if I needed to attend since it was during a time I usually focus on my other jobs (as team leader and area director). Olupah said, come, and as I respect her, I did, even though the meeting was quite late and long and torpedoed the entire day. I'm so glad. What I learned in that meeting was the complex other-side of assisting the desperate. Even an infusion of a few hundred dollars worth of malaria medicine and vitamins can lead to relational fallout. Though our leaders are people of impeccable character and strove to direct every extra vial to the right place, others around them questioned why the medicines were locked in a cabinet with limited access. Suspicions arose. Were we favouring some staff who could profit? Was that bulky shoulder bag because of a dirty uniform being taken home to wash, or stealing medicine? I was floored, and sad, to see the people we trust and respect suffering for their responsible and helpful actions. But that was nothing compared to the actual misery that she, and others, had experienced as the gossip escalated and accusations festered. Similarly this year, the government sent a belated bit of their Ebola windfall cash to our hospital since we were actually on the border and prepared for cases (in spite of dozens and dozens of alerts and tests here, NONE of the Beni-based 2018-20 epidemic crossed this border . . . it's less than 50 miles away!!). That Ebola money led to a lot of discord, questions, accusations, mutiny. In a culture that values equality above most other goods, anyone perceived to get benefit is isolated and vilified as a suspect. In fact at various points I was ready to throw my hands up and decide it was better to just not try to help.

However, the lesson in this kind of situation is to sit back and watch the cultural experts do their thing. This is why we are only part of the partnership. We have access to resources, to donors, to vehicles, to planning and resources. But we don't have the patience, depth, moral authority, capacity to solve widespread jealousy. Thankfully, our Ugandan partners do. I watched as everyone had their say, as the skilled leaders listened, as the conversation turned to ways to bring in help with accountability, as agreements about keys and documentation were reached, as the end note was celebratory and thankful.

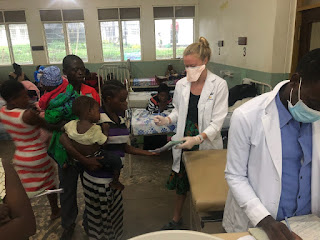

So we live to work another day. Another box of emergency medical supplies. Before we could even get it unpacked, Scott was sending me a nursing student on the run to get a blood transfusion set to save the life of a mother with post-partum-hemorrhage. I found one of our malnutrition patients barely arousable with a low pulse, and the immediate ORS and antibiotics (which he had not received in the days prior due to cost) will hopefully save his life.

Doing good is complex. Unintended consequences abound. Being willing to be inconvenienced, to change, to grow, means we can always learn more. Always do better. We can never assume our interventions, from scholarships to peanut-butter paste, will bring unadulterated joy. But giving up, running away, are cop-out reactions. Instead we are called to keep engaging, inviting the feedback, becoming real partners in a shared endeavour.

However, CSB and all other schools cannot open. The country wide policies are the same: we still have a curfew, no churches, no gatherings, we are enjoined to stay home, to keep distance, to wear masks, and only limited shops are open.

In fact in Bundibugyo we've been studying this problem in health care capacity-the pandemic's impact on health worker burn out, sickness, fear; the lack of supplies and diversion of resources to other places, the stress on marginal health systems; the hesitation of the population to seek care as frightening messages roll out about coronavirus, the ban on public transportation, the curfews, the falling economy, all making care difficult to access. It's a perfect storm we've seen before with Ebola, only this time the winds are pounding globally. We actually have some pretty good data that the potential collateral damage could be greater than the viral damage (as it has been for Ebola), with years of improvement in maternal and child health lost. Quite possible bad-case-scenario (I won't say worst-case, because these are mathematical models of reasonably possible events and 2020 keeps throwing us curve balls), both maternal and child deaths could increase by 38-44% this year. That would be over 2 million extra dead children.

We know that some basic interventions: food for malnutrition, antibiotics, medicines that stop blood loss in labor, a clean delivery environment . . . can prevent much of this slide. A few hundred dollars of such basics serves more than a hundred people. In fact I suppose that many of the 2 million plus lives that the COVID impact will cost could be saved with less than 8 million dollars' investment in the right places.

So the responsible thing, the just thing, would be to use all possible means to shore up the systems that are crumbling, to invest in medicines and food and vaccines that can save lives.

Which is what we do here routinely, and way moreso the last few weeks. Bundibugyo Hospital has a solid team of leaders, and we are privileged to join forces with people who are concerned about how to improve our quality of care. How to stay ahead of the problems. How to work together.

But yesterday, I saw that a meeting for the Paeds ward staff had been called. I texted the in-charge nurse to see if I needed to attend since it was during a time I usually focus on my other jobs (as team leader and area director). Olupah said, come, and as I respect her, I did, even though the meeting was quite late and long and torpedoed the entire day. I'm so glad. What I learned in that meeting was the complex other-side of assisting the desperate. Even an infusion of a few hundred dollars worth of malaria medicine and vitamins can lead to relational fallout. Though our leaders are people of impeccable character and strove to direct every extra vial to the right place, others around them questioned why the medicines were locked in a cabinet with limited access. Suspicions arose. Were we favouring some staff who could profit? Was that bulky shoulder bag because of a dirty uniform being taken home to wash, or stealing medicine? I was floored, and sad, to see the people we trust and respect suffering for their responsible and helpful actions. But that was nothing compared to the actual misery that she, and others, had experienced as the gossip escalated and accusations festered. Similarly this year, the government sent a belated bit of their Ebola windfall cash to our hospital since we were actually on the border and prepared for cases (in spite of dozens and dozens of alerts and tests here, NONE of the Beni-based 2018-20 epidemic crossed this border . . . it's less than 50 miles away!!). That Ebola money led to a lot of discord, questions, accusations, mutiny. In a culture that values equality above most other goods, anyone perceived to get benefit is isolated and vilified as a suspect. In fact at various points I was ready to throw my hands up and decide it was better to just not try to help.

However, the lesson in this kind of situation is to sit back and watch the cultural experts do their thing. This is why we are only part of the partnership. We have access to resources, to donors, to vehicles, to planning and resources. But we don't have the patience, depth, moral authority, capacity to solve widespread jealousy. Thankfully, our Ugandan partners do. I watched as everyone had their say, as the skilled leaders listened, as the conversation turned to ways to bring in help with accountability, as agreements about keys and documentation were reached, as the end note was celebratory and thankful.

So we live to work another day. Another box of emergency medical supplies. Before we could even get it unpacked, Scott was sending me a nursing student on the run to get a blood transfusion set to save the life of a mother with post-partum-hemorrhage. I found one of our malnutrition patients barely arousable with a low pulse, and the immediate ORS and antibiotics (which he had not received in the days prior due to cost) will hopefully save his life.

Doing good is complex. Unintended consequences abound. Being willing to be inconvenienced, to change, to grow, means we can always learn more. Always do better. We can never assume our interventions, from scholarships to peanut-butter paste, will bring unadulterated joy. But giving up, running away, are cop-out reactions. Instead we are called to keep engaging, inviting the feedback, becoming real partners in a shared endeavour.

This is our life: every week or two waiting for the latest rules. This time we got two big releases: in spite of being a border district, public and private transport is now allowed with limited passengers. Wooohooooo.

However, CSB and all other schools cannot open. The country wide policies are the same: we still have a curfew, no churches, no gatherings, we are enjoined to stay home, to keep distance, to wear masks, and only limited shops are open.