Ten days ago, Uganda declared an Ebola outbreak in the centre of the the country. Mubende District and the contiguous districts east and west have now reported 50 cases and 24 deaths. Numerical exactness remains elusive early in an epidemic, because it takes a cluster of deaths to even raise suspicions, and by the time a suspect person reaches a regional referral hospital and the alert doctors there consider testing what looks like malaria (fever, vomiting, diarrhea, some bleeding, extreme weakness) for a hemorrhagic fever virus . . . there is a lot of damage to control. So those 50 cases are actually 31 positive tests; the other 19 are suspected by history. Those 24 deaths occurred in 6 patients among the 31 test-confirmed cases, but we are also counting 18 deaths among the 19 suspected cases. Meaning that looking back a few weeks, at least 18 people who died in the area were already buried in a cluster of families that all have connection to people now testing positive. Uganda has sprung to action. There are press conferences and informative posters urging caution and isolation and good hygiene. Hospitals around the country are setting up isolation wards and setting aside protective gear. We have a Uganda Viral Research Institute that identified the Sudan strain of the virus in the first sample sent, so we didn't have to wait for distant labs. UVRI is supposed to have a mobile lab in Mubende by today. Four doctors, a med student, and an anesthetic officer are among the patients who have tested positive now amongst the 414 contacts being observed.

For us, an Ebola epidemic of this size in this country carries a heavy weight of memory. In 2007, Ebola crossed into our population here in Bundibugyo with a brand new viral strain that took time to identify. At that time there were four of us doctors in Bundibugyo, and we had all seen suspect patients. Two were infected; Scott and I were not. Our dearest friend here, Dr. Jonah Kule, died, while Dr. Sessanga recovered. Bundibugyo lost a treasure in Dr. Jonah, and 4 other health care workers (nurses, eye assistant, clinical officer). That is a long and sorrowful story for another day but it does give us a sobering context for 2022.

Because safety is not our final promise, or goal. Not all prayers for healing are answered.

No one needs to be convinced of that, though we often seem to pretend that it could be true if one were just more holy, more committed, more intelligent, more hard-working. Right now Florida is being stomped by a category 4 hurricane, a powerful violent storm of wind and wave surge and rain. The Americas have had a disproportionately severe outcome from COVID which is now the 3rd leading cause of death in the USA. Not to mention school shootings and the war in Ukraine and rebel attacks and a million small stories of lost babies and unexpected cancer and dwindling parents or grandparents. Grief stalks each and every one of us. In our hearts, we feel like Uganda has had more than her share of grief, so another Ebola epidemic really seems hard.

As a team we continue through Tish Harrison Warren's Prayer in the Night. And this week we got to the phrase, bless the dying. Very poignant for all of us as Ebola percolates in our country (it's not here in Bundibugyo we just feel the fragility of our medical system and are realistic about human behaviours that could lead to dissemination). The Forrest family just traveled to California to the memorial for Kacie's dad who died. And my cousin died this week too. We share the same name (!) and she's just two years older than me, someone who always seemed admirably stylish and hip as we vacationed together growing up, and someone whom I grew to admire on new levels as an adult (though sadly at a great distance) as she faithfully and loyally held onto her family and overcame addiction . . . only to be saddled with early and metastatic cancer.

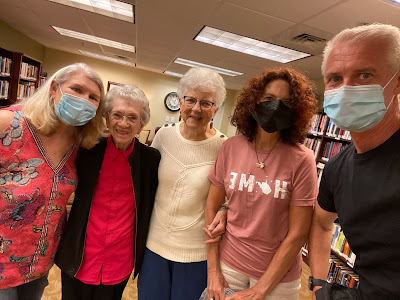

cousin Jennifer far left, last visit with her a year agoWarren writes richly that "bless the dying" in the early church was steeped in paradox: that God can heal but eventually all of us die, that death is our final enemy but also gain, that we are right to hate death while at the same time we embrace in faith the truth that death is not the end. That death, specifically the horrifically painful and unjust crucifixion of Jesus, was the means of the redemption of all things. That on the other side of death, we await resurrection. And yet none of those truths obviate the human experience of grief. We cry. We pray. We wait. We work.

Sitting in 2022, whether in a rainstorm in the southeastern USA or in the Ebola zone in Uganda, this is our hope. Not that we will be spared all suffering and never fall sick or die, but that our dying would be blessed. Blessed one day in dying like Jennifer, in her sleep, in her home, her daughter having arrived that day, after a month or more of goodbyes and preparation. Blessed now by informing our living. May our awareness of mortality paradoxically bring us peace to focus on the important: love, truth, beauty, connection, service. May we let go of pretending, and make space for the presence of reality. Of God. And may we have courage to realise, that is actually what matters and what is promised as we walk through the valley of the shadow of death.

Warren's chapter ends with this:

We are dying, each and all. Yet the kind of blessing we most need is the kind that comes to the dying--a blessing we live our life avoiding, a blessing found only in darkness. In the pace of deepest desolation, we meet God himself.

.jpeg)