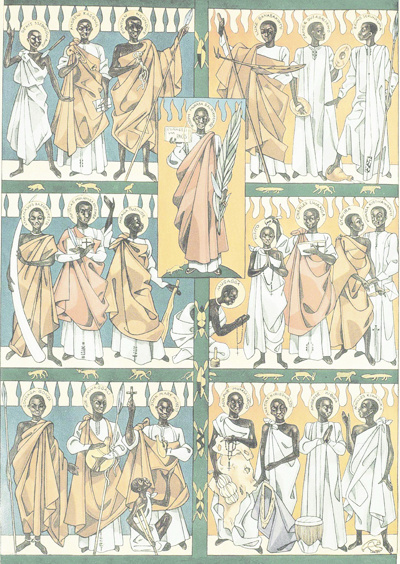

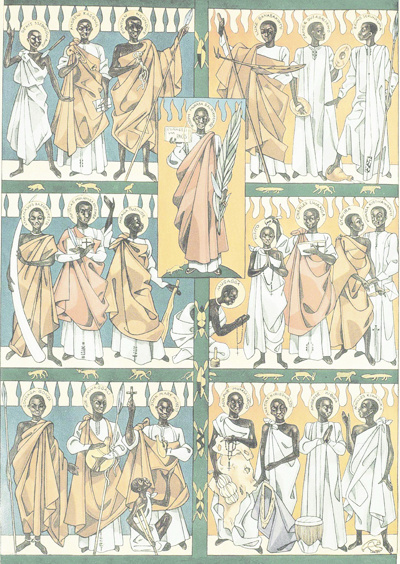

Today Uganda commemorates the boys and men burned to death in Namugongo for their faith, on June 3, 1886. The year before, the Kabaka Mwanga had already killed a missionary James Hannington and a Ugandan Catholic leader Joseph Mkasa Balikuddembe, and up to 45 were killed between 1885 and 1887. But the sheer scale and public spectacle of the 32 martyrs burned on June 3, combined with their courage and conviction as they died, shook perceptions of the new faith. Prior to this event, Christianity could have appeared to be a Western religion associated with the colonial interests of Europe. A perception which no doubt held some truth. What angered the Kabaka to the point of such mass cruelty? The loss of his power over his people. The same thing that angered the rulers of Jerusalem, and Rome, and a thousand places before and since: faith in Jesus took priority in the believers' lives, even over loyalty to the king. They would now weigh their actions, right and wrong, priorities, obedience, on a standard that was outside of and higher than the opinion of the Kabaka. This included the tradition that young male court pages were also the sexual partners of the Kabaka, a practice they realized they could now resist. Jesus always sounded political to those who took his words seriously. Kabaka Mwanga understood that. He felt threatened, and he struck back. The resistance to his sexual exploitation no doubt left him feeling disempowered, but there were also likely good reasons he was worried that if his citizens sided with the new religion they would also side with the British. It was complicated. But the result was not a whole-scale embrace of European rule; it was an eye-opening grass-roots ripple that turned into a wave that said, this is something real. Something African. These 32 went to their deaths singing and praying to God to forgive their oppressors. And their death caused all around them to confront their faith, and to say, this is not a way to gain the world, this is a way to gain your soul.

Uganda's recognition of this event includes two major memorials (one Catholic and one Anglican/Church of Uganda), parades, a University, the national public holiday. Martyr's Day forms a central place in Uganda's story, self-perception, strength. Which is interesting in the 21rst century's obsession with the so-called prosperity gospel, with the constant world-wide fallacy of equating faith and power, Jesus and wealth, right and might. Martry's day preaches the cross. The 32 chose a freedom of conscience that was more valuable than life, an integrity that cost them a horrific painful death. In stark contrast to preachers with personal jets or promises that belief produces health and wealth, the martyrs arrest the attention of the world with a stark holiness: theway of the Kingdom of God is the way of the cross.

This is not a naturally appealing story in any culture. But the improbability provided key evidence that the followers of Jesus transcend any national identity.

Within my lifetime, this story had another Ugandan chapter. Another ruler, Idi Amin, felt threatened by the clergy who questioned his excesses of power. He also sent Christians to their death, notably Archbishop Janani Luwum in 1977.

Uganda's witness to the world powerfully questions blind obedience to the powers that be. Followers of Jesus in many times and cultures have had the conviction and courage to stand up to injustice in the political sphere, and in doing so have met the suffering. Just as Jesus did.

Uganda's recognition of this event includes two major memorials (one Catholic and one Anglican/Church of Uganda), parades, a University, the national public holiday. Martyr's Day forms a central place in Uganda's story, self-perception, strength. Which is interesting in the 21rst century's obsession with the so-called prosperity gospel, with the constant world-wide fallacy of equating faith and power, Jesus and wealth, right and might. Martry's day preaches the cross. The 32 chose a freedom of conscience that was more valuable than life, an integrity that cost them a horrific painful death. In stark contrast to preachers with personal jets or promises that belief produces health and wealth, the martyrs arrest the attention of the world with a stark holiness: theway of the Kingdom of God is the way of the cross.

This is not a naturally appealing story in any culture. But the improbability provided key evidence that the followers of Jesus transcend any national identity.

Within my lifetime, this story had another Ugandan chapter. Another ruler, Idi Amin, felt threatened by the clergy who questioned his excesses of power. He also sent Christians to their death, notably Archbishop Janani Luwum in 1977.

Uganda's witness to the world powerfully questions blind obedience to the powers that be. Followers of Jesus in many times and cultures have had the conviction and courage to stand up to injustice in the political sphere, and in doing so have met the suffering. Just as Jesus did.

No comments:

Post a Comment