Friday the 13th, as America declared a National Emergency, our Serge organisation met to discuss travel policies, lots of phone calls and texts to make decisions and cancellations, the first case of COVID-19 in East Africa was diagnosed in Kenya in a person who had traveled from the USA . . . and life went on in Uganda. Meaning 8 am at the hospital, finding a young child who had been admitted the day before with a viral lung infection (presumably NOT coronavirus, there are so many virae), been on oxygen and convulsing overnight, and was now having intermittent agonal breaths. The shift had just changed, we did what we could which was not enough, and she died. The morning staff meeting, the realisation that no other doctor was in the hospital today (politics, interviews, post-call exhaustion, planned travel). Bouncing between a packed ward and the newly opened NICU. Premature twins on day of life 3, doing what preterm twins do--getting jaundiced and losing a little weight but otherwise vigorous. But a baby admitted overnight whose mother had delivered a twin on the way to the hospital but not been able to get this one out. No records to say how long it took to get a C section or what the apgars were, but the baby was limp, blue on CPAP, with unresponsive pupils. Also dying.

Then back to the ward, facing what the records said was 81 patients but probably was more like 70-some, with what felt like no help. No vital signs charted. No one charting much of anything. Just bed to bed, mattresses on the floor, scribbling in exercise books, talking to parents, doing exams, making decisions, ordering labs and medicines, trying to find the sickest but salvagable. There was something about starting with two deaths and unexpected aloneness in the context of a pandemic that just threw me into despair. I texted a few team mates to pray. Scott sent back an encouraging message. And by grace, we plugged on.

Once I just set myself to see the patients one at a time, to look at the little humans as humans and their parents as parents, to not worry about doing it ALL but just focus on doing the next thing, the day changed. I wasn't alone. There was a nurse in the injection room giving meds, and one in the office writing discharge papers. Later another came to help me get more kids on oxygen. Clovice our every-cheerful BundiNutrition aid was there, and even though he's not medically trained he's faithful and dependable, and recognized two of the sickest patients to call my attention to.

So here is a glimpse of rounds, on a normal day.

Typical section of the ward, when the beds fill patients just add mats and mattresses to the floor.

Ants enjoying the dripped IVF, evidence I suppose that the dextrose label actually DOES include dextrose.

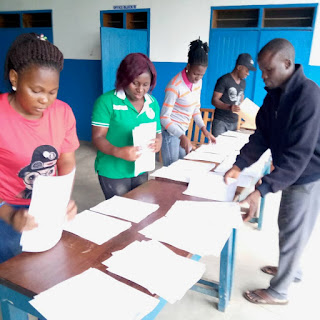

Looking for lab results, discovered dozens from the last few weeks jammed into this drawer.

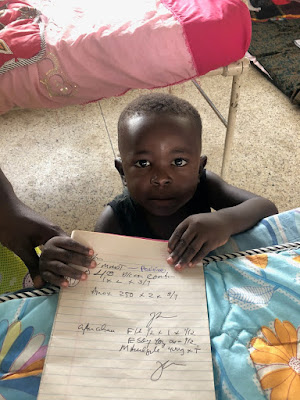

As if being under the Ebola into poster wasn't bad enough, this kid accidentally cut his heel down to bone FOUR DAYS AGO, came to the hospital two days ago and happened to get tested for malaria, which was positive. His hemoglobin was very low as blood poured out of his heel and parasites attacked what was left. Evidently his hand-carried record book got displaced, so until I found him bleeding away nothing had been done yet . . .

She survived malaria with vomiting blood, and a hemoglobin of 1.4 on admission (normal 12). In spite of exceptions like the kid above, we have made good strides on malaria and transfusions. Our nurses can inject artesunate (and ampicillin) and hang blood transfusions. Those three things save a lot of lives actually.

Malaria is so endemic that we try NOT to let anyone go home that was not tested. This boy was ready for discharge, his pneumonia better, but he had a palpable spleen. So I had to finally march him into the appropriate blood testing area and insist, and wa la, malaria. So he'll go home on treatment. Yeah.

More patients. At this point I was about half way through the ward. Malaria, malaria, malnutrition, sickle cell, pneumonia, lots of viral syndomes, abscesses, burns, hit-by piki, and so on.

Don't let sickle cell disease ruin your fashion sense. This hat and smile were so cute.

Sometimes a story just grabs me. A one-year-old wakes up screaming in his home at night, and the mom sees a big black snake. Snakes sometimes come into poorly sealed homes and look for warmth, and when you sleep on a floor mat . . .then the baby moves, the snake panics, and there is a bite. This child's arm was swollen and tender up to the shoulder and we could see the double fang marks. But by Friday she was much better and able to go home. The snake escaped, but hopefully that little reptile brain was scared enough to stay away.

Another fashionable cure. Little girls and spangles. Mirror image G??

This 7 year old is a twin, whom we have followed for several months. She has signs of Kwashiorkor (swollen feet and face, skin lesions, listlessness) which is not typical in her age group. Though she improved a bit on her first admission getting food and malaria treatment, now she has some pneumonia findings, so we decided to treat for TB. With an unaffected twin, it seems to be more than just hunger.

The first NICU admissions were a set of preterm twins . . this one getting some natural phototherapy in his home made incubator (thanks Dr. Marc for all the work into getting this set up, and Kibuye/Tenwek/Caleb Fader for the incubator design). There was a bug floating in the CPAP but the baby looked great.

You might be surprised to know the typical topic of conversation these moments when I am trying to distract and calm an infant or toddler long enough to check their oxygen saturations and heart rate. The mother is usually saying something to the baby like "see your wife here? Are you going to marry her?" and we are all smiling because this is the normal way infants and grandmothers relate. I am not making that up. Literally many times a day I hear proposals from one-year-olds via their mothers.

This is the newest fashion trend sheet, I probably saw four on Friday. Sort of an American nod with the stars and stripes, but a few snowflakes for good measure and a global skyline.

And so we go. Examine, talk, think, write, make a phone call, check a dose, lead the patient to the nurse's room for a blood draw or injection if it just doesn't seem to be happening. On a good day, when someone is praying, I can make eye contact and feel empathy and take time to force my tongue into Lubwisi to explain, instead of rushing and feeling overwhelmed and frustrated. I try to go over the sickest patients with the nurses, to do some teaching. I make lists, and communicate with the doctors who might come over the weekend. It takes about 6-7 hours to get through rounds, meetings, treatments, etc. In between each patient, a generous splash of alcohol hand sanitiser. We only have one oxygen tank and one concentrator. I have to choose which two of the four hypoxic patients get the oxygen. All of this is baseline. Before coronavirus.

We have three young boys with chests like this, consolidated pneumonias on one side. They are breathing at twice the normal rate or more. I can see their ribs as they work hard. This is before coronavirus, as far as we know.

Social distancing, hand hygiene, suspension of travel and gathering . . . these are methods to slow the spread of the pandemic so that the health system can adjust, can cope. But what if your health system already isn't coping?

Today's words from Deuteronomy. This is a global season of wilderness. This is a time we can lean only upon God's provision. And this is a walk of faith that God will bring some good in the end.

This street sign is painted a few hundred meters down the road from us. "Born to win" street. Africa may not have resilient health systems, but we do have resilient people. And always, hope.

(And for another view of life in Bundi, read

this blog about our Orphans and Vulnerable Children scholarship program. Or

this one about cross-cultural realities from our BundiNutristionist.)