Uganda cases are now14, out of 308 tested. We are still in the phase of only suspecting travellers, so if the coronavirus entered months ago and has been persistently and relentlessly spreading, we don't know. So far only one test has been done in Bundibugyo, and it was negative, so we have no idea locally either.

Five minutes ago, the third neighbour/acquaintance of the day came to say that they needed help. Food prices in the market shot up as soon as the first cases were announced. With borders closed, markets limited, movement discouraged, school children sent home, the average person here is not as concerned about dying of the virus as about going hungry. The main cash crop, cocoa, has already become much less valuable as European markets imploded. So our friends say, here we are at home, sitting with nothing, and not sure what we will eat. Uganda is a fertile country but also a crowded one. The average household here will be more able than most places to survive from a garden, from the land, but it will still be hard. Most markets have been closed down.

Every day, almost, the president speaks and announces new restrictions. Last night he canceled all public transport--all buses, matatus, bodas, trucks. Now motorcycles can deliver packages but not people. VERY FEW private cars exist, so this is an effective way to shut off movement. There are road blocks now set up between our town and the border. Questions are asked and the military is serious.

Our teachers spent the week working on take-home assignments to be distributed to our 357 CSB students tomorrow. They had a plan to go tomorrow to seven points around the district, and hand the hefty packets out to the students forced home a week ago. Only now everyone is afraid to do that, lest we be accused of causing unlawful gathering. The government did approve the plan to have teachers get radio time, but with transport shut down, even that might not happen. Wealthier elites will have TV and internet in the cities; our students will have nothing.

Medical care continues, but as expected, patients are afraid too. Maternity was still full. Paeds was down to 100% full, meaning only beds and not the floor. And to add insult to injury, I saw the first case of measles in about six months. Last year this time we were in a major measles pandemic, but the concerted efforts of vaccination teams over the course of 2019 really made an impact. Measles is even more contagious than coronavirus, and deadly. In fact over 140,000 children/year have died of measles the last couple of years, due to failure to vaccinate. So far this year, 20,000 people have died of coronavirus. (Begging the question of, will everyone get a coronavirus vaccine if it becomes available, or not!? The COVID-19 risk to people under age 50 is probably similar to seasonal influenza; how many of those got a flu vaccine this year??). My case yesterday was a 6 month old, meaning he had not yet been old enough to get the vaccine, and missed the special campaigns of 2019. His illness also means that there is active virus circulating in his community. So in the midst of COVID-19 preparedness and anxiety . . . we had to call for another team to go out and investigate measles.

Which illustrates the point of a complex emergency. COVID-19 is here, and it will cause harm directly to many people who will suffer. But it is also already causing collateral damage. How many malaria patients didn't get treatment this week because they were afraid to come to the hospital? How much will measles, or HIV, or gastroenteritis surge as all attention is diverted? How will the economic downturns translate into malnutrition, or domestic violence, or dropping out of school?

And while we track Uganda, and serve Bundibugyo, we also keep our eyes on the global escalation, remembering that the actual cases are probably 10x the confirmed cases (or more). So for our team, there are so many layers of trauma. Hearing and watching our community and friends suffer all around us. Working to prepare for the worst when we know how limited we are. The ever-present possibility of getting sick. Watching other Americans evacuate Africa (not now that it's all closed down, but a few days ago) and choosing to stay, then second-guessing that. Fielding well-meaning queries from family and friends who ask, so, if you get really sick what will happen, and not being able to give reassuringly confident answers. In the wee hours of the morning, thinking, what if I am the small percentage who needs an ICU, which does not exist? Or, how long can we manage if power, or banking, or markets, completely stop? Communicating with family and feeling their pain, jobs lost, restless isolation, canceled plans, looming worry.

These are real questions, and we are real people, who are in this global storm. Most of the times in our life, we slap a prayer onto what we subtly truly trust: the medicine, the expert, the evacuation, the plan. But there are sometimes seasons when our illusion of control is completely stripped away. Preterm labor in a place that at the time had no capacity to care for a preem. Walking with a crowd of about-to-be-refugees towards the Congo border with gunfire behind us. Taking our temperature for 21 days in an Ebola epidemic where we had been exposed, and there was no option to leave. And now. So what is our comfort? That the presence and good intent of God towards us cannot be interrupted by anything, not war, not disease, not edicts, not even death. And though I can type that as truth, I will not pretend that I can feel that in my bones at all moments.

Peter had to step out of the boat into the storm, God's people had to step into the Jordan and run towards the battle, to see the miracles. The ones who said, we can't put our children at risk (Num 14:3), did not live to see the promised land. So day 5, here we are, putting in a toe and holding our breath for the rescue.

Five minutes ago, the third neighbour/acquaintance of the day came to say that they needed help. Food prices in the market shot up as soon as the first cases were announced. With borders closed, markets limited, movement discouraged, school children sent home, the average person here is not as concerned about dying of the virus as about going hungry. The main cash crop, cocoa, has already become much less valuable as European markets imploded. So our friends say, here we are at home, sitting with nothing, and not sure what we will eat. Uganda is a fertile country but also a crowded one. The average household here will be more able than most places to survive from a garden, from the land, but it will still be hard. Most markets have been closed down.

Every day, almost, the president speaks and announces new restrictions. Last night he canceled all public transport--all buses, matatus, bodas, trucks. Now motorcycles can deliver packages but not people. VERY FEW private cars exist, so this is an effective way to shut off movement. There are road blocks now set up between our town and the border. Questions are asked and the military is serious.

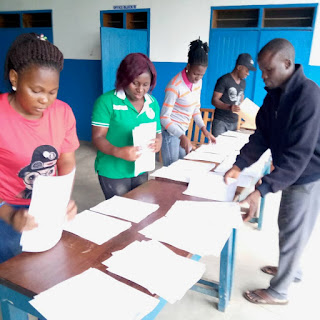

Our teachers spent the week working on take-home assignments to be distributed to our 357 CSB students tomorrow. They had a plan to go tomorrow to seven points around the district, and hand the hefty packets out to the students forced home a week ago. Only now everyone is afraid to do that, lest we be accused of causing unlawful gathering. The government did approve the plan to have teachers get radio time, but with transport shut down, even that might not happen. Wealthier elites will have TV and internet in the cities; our students will have nothing.

That is the floor, something that is usually covered with mattresses and mats and blankets and kids

Medical care continues, but as expected, patients are afraid too. Maternity was still full. Paeds was down to 100% full, meaning only beds and not the floor. And to add insult to injury, I saw the first case of measles in about six months. Last year this time we were in a major measles pandemic, but the concerted efforts of vaccination teams over the course of 2019 really made an impact. Measles is even more contagious than coronavirus, and deadly. In fact over 140,000 children/year have died of measles the last couple of years, due to failure to vaccinate. So far this year, 20,000 people have died of coronavirus. (Begging the question of, will everyone get a coronavirus vaccine if it becomes available, or not!? The COVID-19 risk to people under age 50 is probably similar to seasonal influenza; how many of those got a flu vaccine this year??). My case yesterday was a 6 month old, meaning he had not yet been old enough to get the vaccine, and missed the special campaigns of 2019. His illness also means that there is active virus circulating in his community. So in the midst of COVID-19 preparedness and anxiety . . . we had to call for another team to go out and investigate measles.

Measles rash in an otherwise quite robust 6-month-old

Which illustrates the point of a complex emergency. COVID-19 is here, and it will cause harm directly to many people who will suffer. But it is also already causing collateral damage. How many malaria patients didn't get treatment this week because they were afraid to come to the hospital? How much will measles, or HIV, or gastroenteritis surge as all attention is diverted? How will the economic downturns translate into malnutrition, or domestic violence, or dropping out of school?

And while we track Uganda, and serve Bundibugyo, we also keep our eyes on the global escalation, remembering that the actual cases are probably 10x the confirmed cases (or more). So for our team, there are so many layers of trauma. Hearing and watching our community and friends suffer all around us. Working to prepare for the worst when we know how limited we are. The ever-present possibility of getting sick. Watching other Americans evacuate Africa (not now that it's all closed down, but a few days ago) and choosing to stay, then second-guessing that. Fielding well-meaning queries from family and friends who ask, so, if you get really sick what will happen, and not being able to give reassuringly confident answers. In the wee hours of the morning, thinking, what if I am the small percentage who needs an ICU, which does not exist? Or, how long can we manage if power, or banking, or markets, completely stop? Communicating with family and feeling their pain, jobs lost, restless isolation, canceled plans, looming worry.

These are real questions, and we are real people, who are in this global storm. Most of the times in our life, we slap a prayer onto what we subtly truly trust: the medicine, the expert, the evacuation, the plan. But there are sometimes seasons when our illusion of control is completely stripped away. Preterm labor in a place that at the time had no capacity to care for a preem. Walking with a crowd of about-to-be-refugees towards the Congo border with gunfire behind us. Taking our temperature for 21 days in an Ebola epidemic where we had been exposed, and there was no option to leave. And now. So what is our comfort? That the presence and good intent of God towards us cannot be interrupted by anything, not war, not disease, not edicts, not even death. And though I can type that as truth, I will not pretend that I can feel that in my bones at all moments.

Peter had to step out of the boat into the storm, God's people had to step into the Jordan and run towards the battle, to see the miracles. The ones who said, we can't put our children at risk (Num 14:3), did not live to see the promised land. So day 5, here we are, putting in a toe and holding our breath for the rescue.

2 comments:

Jennifer, watched Dr Segal, NYU, I believe, and he said that seeing African countries in the Southern Hemisphere just now entering the winter months and beginning to incur Covin-19 cases might indicate seasonality of the virus. Suppose best to not be complacent, but prepared in every way possible with limited resourcesvat your disposal. Hopefully you have access to CDC guidelines: www.cdc.org

Medical scientists worldwide are working feverishly to develop vaccines as well as therapeutic treatments for infected patients. Meanwhile, hope you have ample supplies of masks, plastic gloves, hand soaps, disinfectants etc for your and Scott’s own protection. If you’re continuing to take anti-malaria medications, hopefully some of these might soon prove to be beneficial against CV.

Remaining prayerful for you,

Fred

Greetings, Jennifer, from Parot village, Aweil East, South Sudan. I have followed your blog for years and always appreciated it, but do so even more now, in this current crisis. You express so well many things I have been thinking or feeling. Thank you for your transparency. May the Lord uphold you and give you continued grace, wisdom and strength in your many responsibilities. Jan B, Cush4Christ

Post a Comment